I want to introduce you to a place. When you finish reading this, I want you to have a sense of what makes it so special, and a subtle but persistent desire to go there. So do as Sam Jackson says, and hold onto your butt. By the time I’m done, you’re going to RSVP with a resounding “hell-yes.”

The first thing that hits you is the smell. It’s that smell you get when you drive by a freshly-mown baseball field in some bucolic American landscape. This forest reeks of it. The aroma of life, growing and damp, fills the cavities of your sinuses until you feel suffused by it. That is the smell of one of the most productive biomes on the planet. It is the smell of ancient trees, some almost 1,000 years old, making our use of the term “millennial” feel shallow and insufficient.

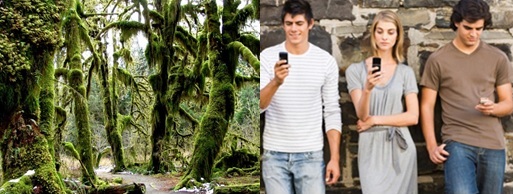

The ground underneath your feet is soft and springy. It feels as if it were charged with energy, waiting to manifest itself as a tree, or a wildflower, or a particularly rambunctious squirrel. If you visit when there aren’t many people around, you’ll hear the soft “pitter-patter” of condensation dripping from leaf to leaf, making its Rube-Goldberg descent through the panoply of trees. The sonorous tone of an elk bugle pierces the quiet stillness, a bold announcement of pride and territory. And when the morning fog clears away, your eyes will drink a scene of green and glory.

If you’re fortunate enough to experience this sensation for yourself, you’ll have found yourself in the temperate rainforests of North America. That’s right: there is a massive rainforest mere hours from Seattle, far away from the tropics. I work in a section of the largest temperate rainforest in the world, which stretches from the Pacific Northwest to southern Alaska. A unique combination of abiotic and biotic factors creates the perfect conditions to allow for unmitigated growth.

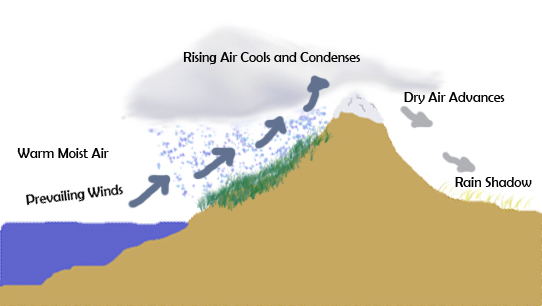

The most noticeable of these factors is the rain. Moisture-laden air from the Pacific Ocean is swept east by large-scale weather patterns. As these air masses climb the mountains near the coast, they expand and cool. Under these conditions, they can no longer hold the water carried in from the ocean. This moisture is dropped as rain on the coastal-facing side of the mountains.

Above, you’ll see how a rain shadow forms. The much-cooler name “storm shadow” was already taken. Image: Atmoz

Imagine it like this: water is dissolved in the air, just like sugar is dissolved in tea. You can dissolve more sugar in hot tea than in cold. Likewise, warm air can hold more water than cold. When air passes over the ocean, it gets warmed by the sun, and a great deal of water is dissolved into it. Once it hits land, the air cools, and it cannot hold as much water (just as a cold cup of tea cannot dissolve as much sugar). The water condenses into rain, providing the massive amount of precipitation that feeds this ecosystem. This is the reason areas along the Pacific coast receive huge amounts of rain. Some areas of the Pacific Northwest receive over 140 inches of rain a year. That’s enough to cover a one-story house, but not quite enough to drown a giraffe.

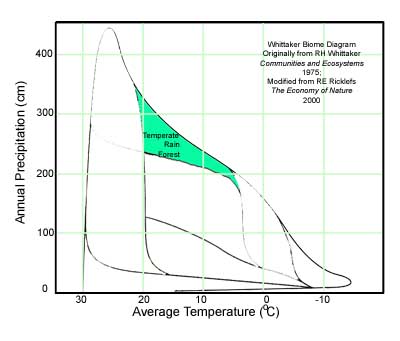

But a temperate rainforest is more than just an abundance of water. Those of you who live a more hedonistic lifestyle may already be familiar with the idea of temperance, or moderation. The temperate in temperate rainforest refers to the fact that it never gets excessively hot or cold (think light sweater weather). The average temperature is somewhere between 4 and 12° C (39 and 54° F). Summer days in excess of 90° F are rare, and a Pacific Northwest winter is mild, with few freezing events. These abiotic factors – abundant rainfall and moderate temperature – create the ideal conditions for explosive plant growth.

The so-called “sweet spot” of terrestrial ecology. Image: Marietta College

I’ve heard some of my fellow rangers compare the masses of moss glommed onto trees to veils or even chandeliers. In my mind this evokes the image of some grand Gothic cathedral, filled with lighter-than-air flying buttresses and intricate filigree; green, verdant, and powerful. What is this power? It’s renewal. It’s the freight-train force of growing things, inexorably rising from the earth. Its pillars of living wood that would take ten people to encircle. Life is inevitable here, as evidenced by the mosses and epiphytes that cling heartily to even the smallest branches.

Natural archway on the Hoh River Trail. Image: Terri Lundberg

For Lord of the Rings Lovers, this is place makes Fangorn and Lothlorien look desolate. For those of you grounded in reality, there is more organic matter in this ecosystem than any other on the planet – about 500 tons of organic matter (both living and dead) per acre (link). Keeping with the giraffe as our unit of measure, that density of life is equal to having 30 giraffes on a tennis court.

A Tower of giraffes. I sh*t you not.

Much of this biomass is stored in the gargantuan trees, which are up to a thousand years old. Think about that: these trees were seedlings when people were worried about the Y1K bug, which was probably an actual bug that was going to eat their crops.

It is a little counterintuitive that despite the enormous tangle of life, biological diversity is relatively low. There are only about 50 species of plants in the Pacific Northwest temperate rainforest (link), a level of biodiversity that is dwarfed by this ecosystems tropical counterpart, where you can find hundreds of plant species (link). The most abundant species in the temperate rainforest are conifers; evergreen trees that reproduce through cones. Within this group, four species comprise almost all the trees in the forest: Sitka spruce (Picea sitchensis), western hemlock (Tsuga heterophylla), western redcedar (Thuja plicata), and Douglas fir (Pseudotsuga menziesii). If you remember these four species, people in the Pacific Northwest will think you’re a wizard of tree ID, a veritable Linnaeus of modern times.

He holds the dichotomous key… to my heart. Original Painting: Alexander Roslin; Image: Alphazeta

Tucked in and among these needled giants are a few species of deciduous tree. Most prominent among these is the big leaf maple (Acer macrophyllum). These maples boast leaves the size of dinner plates, large enough to give the sugar maple leaf on the Canadian flag insecurity issues. The branches seem to grow in any direction but straight up, forming a tangled network of interlaced limbs. Beneath these voluminous boughs stand a smaller sister species, the vine maple (Acer circinatum), growing as an understory shrub or bush. By the time sunlight filters through these profuse layers of needles and leaves, it is tinted a quiet, deep green.

But what really stands out in the temperate rainforest are the epiphytes – plants that grow on the surface of other plants. In environments where precipitation is scarce, plants must put roots into the ground and compete for meager water resources. Moisture is so readily available in the rainforest that epiphytic plants can obtain their water and nutritive requirements from air, rain, and organic debris (known as humus).

Epiphytes in the temperate rainforest can be roughly divided into three groups: mosses, lichens, and liverworts. Almost every surface is encrusted in some form of epiphytic life. Just take a moment to let that sink in: there is so much potential for life in the temperate rainforest, that plants grow on other plants.

Visitors often ask me if these epiphytes are harming the trees they grow on. That is to say, are they parasitic? The answer is a resounding “hell no!” Parasitic plants invade their host tree, sucking it dry of nutrients. The human equivalent would be that dude you knew from college who just needed to “crash” for a couple of days and ate all your goddamn Honey Bunches of Oats.

Epiphytes are the good roommate who comes in and takes over that extra room you weren’t really using anyway. And just like the good roommate who brings home groceries from time to time, epiphytes can help the tree thrive. Their large surface area provides a place for fog to condense during the relatively rain-free summer months. This condensation supplies the host tree with moisture during scarce times (link). The rainforest is literally blanketed in these good-guys, combing the air for moisture and adding to the green mass of life that makes its home here.

Unfortunately, the same things that make this ecosystem so unique and splendid also make it a prime target for exploitation. Temperate rainforests are a veritable gold mine for the timber industry. These areas have been extensively logged for decades, all the way back to before World War II.

It was used to build the DH.98 Mosquito, a plane so badass it pissed off Hermann Göring. Image: Donor S. Southwell

In Oregon and Washington, about 10% of the pre-industrial logging rainforest remains. Many species make their habitat in old-growth forest, which can take centuries to rejuvenate. When landscapes are denuded of their plant life, widespread erosion follows. This action deposits excess soil particles (called silt) in streams that serve as important spawning grounds for anadromous fish like salmon and trout.

What does all this mean for us? The temperate rainforest provides many ecosystem services which support the human communities around them. Healthy ecosystems prevent erosion than can harm property and life, especially in the rain-soaked regions in which they’re found. The rainforest is also a treasure-trove of biodiversity. Over 7,000 medicines have been derived from plant sources (not necessarily from the temperate rainforest), including the malaria remedy quinine (Cinchona officinalis) and the human steroid precursor diosgenin (Dioscorea villosa). Somewhere in the tangle of trees and mosses may be the next chemotherapy agent or a treatment for high blood pressure.

But there is more to the rainforest than what we can extract from it. On the Olympic Peninsula, the National Park Service works with eight local Native American tribes to preserve and perpetuate the cultural traditions that evolved here. School groups come to gain invaluable hands-on experience in ecology and biology. Scientists study these forests to learn more about how climate change will affect these ancient ecosystems. This is to say nothing of the economic benefit. According to the Park Service, visitors to Olympic National Park in 2012 brought approximately $220 million dollars into communities near the park, supporting over 2,700 jobs. As attendance increases, this number is poised to continue growing. And these are jobs that won’t disappear when the logs are used up. As long as the majestic rainforest survives, people will come from all over the globe to partake in its beauty and wonder. In preserving these diverse ecosystems we ensure our role as caretakers and beneficiaries of the natural world.

If you are American, you own this. I cannot stress this fact enough. Image: Natalia Bratslavsky

Although the closest rainforest may be hundreds or thousands of miles away from you, there are still steps you can take to protect them. By and large, I am just going to reiterate common-sense recommendations that you have probably already heard. Make steps to reduce consumption of forest-derived products like wood and paper.

- Instead of buying new furniture seek out second-hand stores such as Goodwill and Habitat for Humanity ReStore. These items not only reduce the demand for new forest products, but also have more character and are a joy to refurbish. Plus, your significant other will inevitably find your ability to fix things attractive.

- Reduce paper consumption by opting for paperless billing or choosing an online newspaper subscription.

- Bring reusable bags to the grocery store. The minute it takes to remember to bring the bags with you isn’t so bad when compared to the time, energy, and water that goes into making billions of plastic and paper bags every year.

These small but significant changes to your day-to-day routines translate into substantial benefit for rainforests you may never even see.

Fourteen million trees are cut each year to meet the U.S. demand for paper bags. Do you want to deprive Bob Ross of happy little trees? DO YOU? Image: Bob Ross Inc.

But that’s the point of this article: get out there and see your rainforests! Many of these places have been protected so that you can enjoy them first-hand. Here are some tips to help you get out there. If you live on the east coast, the nearest temperate rainforest is probably only a one-day drive away, in the southern Appalachian Mountains. The best place to find this ecosystem is in western North Carolina/eastern Tennessee, including:

- Pisgah National Forest

- Nantahala National Forest

- Chattahoochee National Forest

- Gorges State Park

Some high-altitude areas of Great Smoky Mountains National Park receive enough rainfall to be considered temperate rainforests as well (and entrance is free!). If you don’t live this close to the Appalachians, then you might have to get on a plane. Olympic National Park in Washington protects the wettest area of the continental United States, where about 140 inches of rain falls annually. The most popular destinations include:

- Bogachiel River

- Hoh River

- Quinault Rainforest valleys

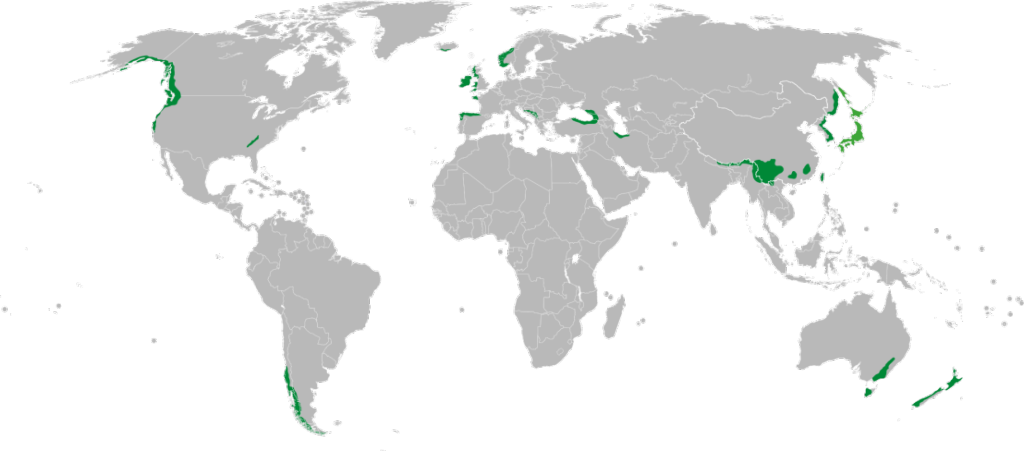

While you’re in the area, you can pay a visit to some of the most rugged protected coastline in the country, and view vast alpine glaciers from Hurricane Ridge. If you’re reading this outside the United States thanks to the wonders of the internet, do not fear. Temperate rainforest can be found on every continent (except the really cold one at the bottom). Look no further than:

- Valdivian and Magellanic forests in Chile

- Knysna-Amatole forest in South Africa

- Fragas do Eume in Northern Spain

- Colchian forests of Turkey

- Taiheiyo rainforests of Japan

Global distribution of temperate rainforests. Image: KarlUdo

If I’ve done my job well, you are now doing the mental arithmetic to figure out just how soon you can make it to the temperate rainforest. It may not be today, tomorrow, or even the next few months. But sooner or later, you’re going to make it. The smell of growing things will permeate the air around you. Green-tinged light will dapple your skin (or, more likely, it will be raining). Your feet will rest in cool, clear water that has percolated through mountain and soil. In the immortal words of Hauser in Total Recall, “Now, this is the plan. Get your ass to [the forest]!”

Connell, JH. Diversity in tropical rain forests and coral reefs. Science 1978. 199(4335):1302-1310. link.

Franklin, JF. Structural and functional diversity in temperate forests. Biodiversity. National Academy Press: Washington, DC, pg 166-175. link.

Nadkarni, NM. Biomass and mineral capital of epiphytes in an Acer macrophyllum community of a temperate moist coniferous forest, Olympic Peninsula, Washington State. Canadian Journal of Botany 1984. 62(11):2223-2228. link.

Noss, RF., ET LaRoe, and JM Scott. Endangered ecosystems of the United States: a preliminary assessment of loss and degradation. U.S Department of the Interior: Washington, DC pg 1-2. link.

Schoonmaker, P. Terrestrial vertibrates. The rain forests of home: profile of a North American bioregion. Island Press: Washington DC pg 104. link.