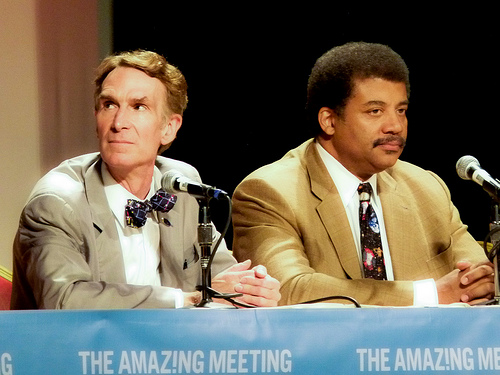

Featured image: Two great American science communicators. Photo credit: Jamie Bernstein

Over the past months, I went to several scientific conferences* on a covert mission. While I was technically there to learn and to discuss my work, I wanted to find out why so many academics avoid engaging with the public about their research.

I ambushed scientists at happy hours, in lounges set up for networking, and other social events. Every chance I had, I asked, “Do you try to engage with a broad, non-scientific audience about your research and ideas?”

While many scientists I talked to thought scientific communication and engagement were important, they didn’t do it themselves. When possible, I asked why they didn’t. Here are the most common responses:

- Concern for reputation: Many believed that scientists lose their impartiality if they advocate for a cause, or that they would be humiliated if they say something incorrect. Some feared political backlash, a reasonable concern since zealous politicians have tried to discredit climate scientists, accusing them of fraud and trying to subpoena their emails.

- Lack of confidence: Many academics haven’t received any training on how to communicate their research to the general public. As for science outside of their research, they acutely feel the lack of their own knowledge in the specific details of similar disciplines, and thus feel inadequate about their own understanding of those topics. They also fear that people wouldn’t listen.

- Not a good use of time: Many academics are overworked as it is. Plus, science communication is not part of their job and is not incentivized. They also felt that they could get more accomplished if they focused on their research.

I have some sympathy for these reasons, but I don’t think they’re good enough. Here’s why.

Since much of the public doesn’t have extensive scientific training, I think that scientists have a right (maybe even an obligation) to add their well-informed ideas into public debate. This debate is happening with or without scientists anyway, so adding an informed opinion improves the quality of the conversation even if that opinion is not perfect. For example, many researchers I talked to were microbiologists. They understand the dangers posed by antibiotic resistance. They may not directly study antibiotic resistance or know the most cutting edge techniques in the field, but they understand that something needs to be done, and some options are important to support to mobilize the public into action – like phasing out use of antibiotics for livestock growth promotion. (A policy change that is now being implemented due in part to the publicizing of relevant information by concerned scientists!). This high baseline of knowledge extends to other important topics, like germ theory, vaccines, and genetically modified organisms.

Therefore, I did not expect that concern over lack of knowledge and being wrong underlay many of the reasons not to engage. Making mistakes, failing, being wrong: these are integral parts of research – ones that scientists use to hone their ideas. Furthermore, these failures can have positive side effects: Accidental discoveries based on failed experiments litter the annals of scientific history. Mistakes can shape scientists into better thinkers by forcing them to reevaluate their thought process, pushing them to be more innovative and productive. In my mind, the same thinking should apply to engagement efforts.

Thus, I was surprised when one of the most consistent pieces of advice I got from my conversations was this: “Don’t engage until you have a solid position. A tenured professorship should be sufficient.”

Assuming optimal circumstances (and that we want to go into academia at all), that’s at least a decade away for me and many other graduate students. As has been discussed extensively, the likelihood of tenure is pretty low. Many young scientists interested in science communication don’t want to wait that long. I also don’t buy the ‘wait until you’re established’ argument. If one receives no training before getting to that point, it seems to be that one would be less inclined to try to engage. After all, the stakes would be much higher. If, as a student writing for a blog, I make a mistake, my opinions carry less weight, and my reputation probably will not be made or broken based on what I say here. If, as a tenured professor, I said something incorrect or something open to misinterpretation to a media outlet, the cost of public humiliation could be high. (Not that it has to be. See Neil deGrasse Tyson’s graceful response to his public mistake regarding DeflateGate).

Perhaps a reason why older academics don’t often engage. From Saturday Morning Breakfast Cereal.

Reflecting on what I learned, it seems that academics are in a tough position. Scientific communication is thought to be important, but most academic scientists won’t do it for the reasons I’ve discussed. As a result, there’s also an unwillingness to train future academics on how to engage: maybe because those skills aren’t valued in our current system, and also because current instructors lack those skills in the first place.

This is a tough cycle to break. As an academic, it’s easy to hide in the ivory tower and avoid interacting with the public. Indeed, that’s a viable decision, and one that academics should be able to choose if they want. But failing to engage leaves an information void that will be filled: the ‘debates’ over climate change, evolution, and vaccines make this clear. It’s not necessarily the duty of academics to engage with the public. However, if they are concerned about the translation of their research to the public, one way to help ensure the accuracy of that information is to play a more active role in disseminating it. (Here’s a great article that discusses how to engage as a scientist).

Despite these challenges, many young scientists are willing to engage in all sorts of ways: volunteering their time at schools, writing articles, making informational videos, and doing other cool stuff to both teach and learn from the general public. While I’m no expert, I’ve found that engaging in scientific communication helps me better understand my own research and how to think critically about questions outside of it. For these reasons alone, I think these efforts are valuable, and should be supported both in and outside the academic community.

Just like with the trials and errors of research, when scientists choose to engage, they will make mistakes. They’ll say something wrong, or something that can be misinterpreted. Then, they’ll be forced to change how they communicate based on what they learned, new evidence, and/or clever arguments.

Communicating scientific ideas is challenging. Try hard. Fail. Evaluate why, make appropriate changes, and try some more.

That’s science.

*Note: One of these conferences did specifically focus on science communication and engagement.

Originally posted on the MiSciWriters blog

References:

Alberts, Bruce, et al. Rescuing US biomedical research from its systemic flaws. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 111.16, 5773-5777 (2014) DOI